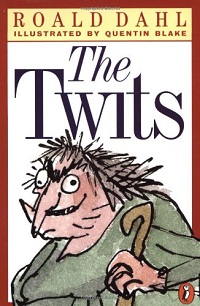

Even by the standards of writer Roald Dahl, The Twits starts out on an unusually disgusting note, with a rant about beards followed by an overly detailed description of just what a certain Mr. Twit has in his, since he has not cleaned it for years.

I have to strongly, strongly suggest not eating during the reading of this passage or indeed the rest of the book, which is filled with enough revolting descriptions to delight the most hardened, YAY THAT’S SO GROSS kid, and turn the stomachs of the rest of us. I’m also not entirely sure what led to this sudden rant against facial hair on the part of Roald Dahl, but I can say that it, and his later descriptions, have the distinct sense of someone really trying to get everything that irritated him (spaghetti, hunting, guns) described in the most disgusting way possible, as if to purge everything nasty from his brain. At least until it came time to write the next book.

The beard description is our introduction to the really horrible Mr. Twit, married to the equally horrible Mrs. Twit. Their idea of marriage appears to be one long series of practical jokes on each other: Mrs. Twit scares Mr. Twit by leaving her glass eye in his glass. In fairness to Mrs. Twit, given the state of Mr. Twit’s beard, she might well have assumed that he would not be overly concerned with any of the sanitary implications of this. Mr. Twit retaliates with a frog in his wife’s bed. Mrs. Twit puts living worms in her husband’s spaghetti. (I repeat: don’t attempt to read this book while eating.) And so on. This may be the worst marriage in children’s literature ever, softened only by the realization that the jokes do make the Twits laugh. And that I can’t help but feel both of them deeply deserve each other.

Even apart from this and the refusal to ever clean his beard (for YEARS), Mr. Twit is the sort of horrible person who puts glue on a dead tree in order to trap birds and small boys for supper. (The cheerful embrace of cannibalism is yet another sign that the Twits? Just AWFUL.) Also, he’s forcing some poor monkeys to practice for the circus upside down which means they can barely get enough to eat. And they are stuck in an awful cage. Like so many of Dahl’s protagonists, they seem completely helpless.

Dahl probably didn’t intend it this way, but the monkeys are, in a way, somewhat like the Oompa-Loompas of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory: taken from Africa to work for white owners, imprisoned in a specific location. Of course, the Oompa-Loompas like their work, and the monkeys do not, and the Oompa-Loompas soon learn to speak English, while the monkeys are unable to speak to any of the local animals until a bird arrives from Africa able to work as a translator.

Anyway, not surprisingly, at that moment, the monkeys finally decide that they can’t take it anymore, and with the help of the birds, enact their revenge. It works with perfect, solid, kid logic. Oh, as an adult I can come up with about a thousand practical reasons why the revenge wouldn’t work (even aside from the idea of monkeys and birds working together to enact said revenge), but from the point of view of a child, it makes absolute sense.

Having Mr. and Mrs. Twit be such horrible people helps on another level as well. I could feel a twinge of pity for some of Dahl’s other villains (not much) or at least feel that as awful as they were, they didn’t perhaps deserve that. But the Twits frankly are even worse than most Bond villains (who at least employ people and therefore help to stimulate the economy, plus frequently pour lots of money into trade and weapons development, more economic stimulus), and are about the only villains I can think of with fewer redeeming factors than Sauron, so watching them suffer is kinda satisfying.

Kinda.

Because, for all of my complaints about their innumerable failings and mean tempers and everything, Dahl also tells us that Mrs. Twit, at least, didn’t start out this way. Admittedly, he is telling us this as part of a very nice moral lesson for kids—mean, ugly thoughts will turn you into a physically ugly person, and good thoughts will always make you look lovely. That is a very nice idea, all the nicer for being completely untrue in my experience—I can think of plenty of people who had many mean, ugly thoughts indeed, but looked just fine on the outside. (Dahl was to reverse gears on this idea completely with The Witches.)

But anyway, Mrs. Twit, at one point, seems to have been a decent enough person. And now, well, she isn’t. Dahl doesn’t give us enough information to know why, or what happened, and, as I noted, I’m not inclined to feel too sympathetic towards any adult who thinks that tricking a spouse into eating live worms is amusing. But I had a twinge or two. Just one or two. If none at all for Mr. Twit.

I should hate this book. I really should. It’s disgusting and the two major characters are horrible and mean and nasty and, as I mentioned, parts of it are not exactly credible. But at the same time, like Dahl, I’m inclined to be somewhat more sympathetic towards the animals, and I couldn’t help cheering when the monkeys decided to take their revenge. I suspect this is another book that reads much better when you are very young and think worms in food are really funny, but if you are young, it might be a decently repulsive read.

Mari Ness is now looking at her spaghetti very very carefully. She lives in central Florida.